El Cine Latinoamericano y Yo

The Austin Film Society's latest Essential Cinema Series, "CineSur: Films of Latin America," begins tonight at 7 pm with Zona Sur at the Alamo Drafthouse on South Lamar.

In 1962 or 1963, when I still couldn't vote or legally drink in a bar, I lived just a few blocks from the Teatro Panamericano in Dallas, the principal Spanish-language movie theater in el barrio (often dismissively referred to by non-Spanish-speakers as "Little Mexico"). The Panamericano was a beautiful building constructed for the Dallas Little Theatre in the 1930s, and was later purchased by the enterprising J.J. Ródriguez in 1943. While I was more frequently at other theaters experiencing Fellini, Antonioni, Truffaut, Godard, Kurosawa and the products of a dying Hollywood, I have fond memories of seeing Mexican films at the Panamericano.

Macario (Roberto Gavaldón, 1960) was haunting and mystical, while Los hermanos Del Hierro (My Son, the Hero, Ismael Rodríguez, 1961) was an unforgettable Western. While I didn't always understand the humor of Tin Tan and Resortes, I loved watching Cantinflas, who was somewhat reminiscent of Chaplin. There were also pre-post-modern movies featuring mashups of legendary monsters, beguiling space creatures and masked wrestlers, but I was still a novice cineaste, and thus far too snobbish to see the delight inherent in such films. That awareness wouldn't happen until 40 years later, but I still cringe when I meet people who think those hilariously awful movies are Mexican cinema.

Throughout the 1960s, I was in Mexico nearly every summer. Naturally my friends wanted to see foreign films (i.e., American films). The era of classic Mexican cinema (La Época de Oro, approximately 1936-1957) had passed. Only toward the end of the '60s would a more radicalized, sexually liberated, university educated, anti-Hollywood group of directors appear. I never could have imagined that one day I would be bringing those directors –- Jaime Humberto Hermosillo, Arturo Ripstein and Felipe Cazals -– to Austin to present some of their powerful films. In 1966-1968, I was at UT Austin getting my M.A. in English, with a minor in film studies, reportedly only the fourth person in the history of the English department to be allowed that minor.

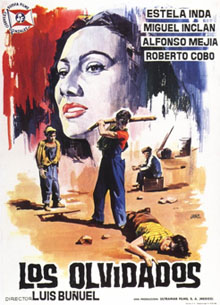

Among the literally hundreds of amazing films I saw in those two-and-a-half years were some Luis Buñuel films, including Los Olvidados (The Young and the Damned, 1950) and El Ángel Exerminador (The Exterminating Angel, 1962). There were also gut-punching films from the Cinema Novo movement of Brazil, such as Vidas Secas (Barren Lives, Nelson Pereira dos Santos, 1963) and Black God, White Devil (Deus e o Diabo na Terra do Sol, Glauber Rocha, 1964). I taught at the Universidad de Puerto Rico (Mayagüez) in 1969-1970, but there were certainly no radical Latin American films being shown there. It was a very tense period, and the government avoided anything which could stir up protests. So, I saw lots of second-rate American films and a few good European ones.

Among the literally hundreds of amazing films I saw in those two-and-a-half years were some Luis Buñuel films, including Los Olvidados (The Young and the Damned, 1950) and El Ángel Exerminador (The Exterminating Angel, 1962). There were also gut-punching films from the Cinema Novo movement of Brazil, such as Vidas Secas (Barren Lives, Nelson Pereira dos Santos, 1963) and Black God, White Devil (Deus e o Diabo na Terra do Sol, Glauber Rocha, 1964). I taught at the Universidad de Puerto Rico (Mayagüez) in 1969-1970, but there were certainly no radical Latin American films being shown there. It was a very tense period, and the government avoided anything which could stir up protests. So, I saw lots of second-rate American films and a few good European ones.

It has taken many years to fill in the 1969-1970 gap in my cinema knowledge. Living in New York City (1970-1973), I was just as intrigued by theater, political activism, art, music and life as by film, so I was rather selective. Along with European and Asian cinema, I saw some of the post-revolution Cuban films, such as Memories of Underdevelopment (Memorias de Subdesarrollo, Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, 1968) and Lucia (Humberto Solas, 1968). But it was El Topo (Alejandro Jodorowsky, 1970) which proved something even more radical was happening in Mexican cinema.

Returning to Austin in 1973 to begin a 25-year career as Professor of Radio-TV-Film at Austin Community College, I reveled in the rise of the Chicano movimiento. Austin had become a far more interesting place than it had been while I was in graduate school. There were some good Mexican films at the Montopolis Drive-In and for a short while, at the State Theatre. But the arrival of videotape hastened the death of Spanish-language movie theaters in Austin and throughout the Southwest. Rental stores like Acapulco Video offered hundreds of great, mediocre and awful films from Mexico. I was finally able to see many of the classics from the 1940s and '50s. Getting to know Dr. Charles Ramírez-Berg in the 1990s helped put so much of this material in context.

In 1988, I went to Cuba for a month and visited the famous ICAIC film offices, where I seemed like a demented Yánqui buying posters and BetaMax tapes of several dozen Cuban films. The following year in Dallas, I had the good fortune of meeting Jaime Humberto Hermosillo, who was presenting Dona Herlinda and Her Son (Dona Herlinda y su Hijo, 1985), the first openly gay film to be made in Mexico. At his invitation, I attended the Guadalajara Film Festival, where I was immersed in Mexican cinema for a week.

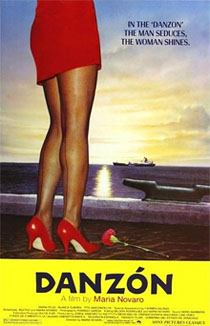

In 1997, I spent a week in Mexico City while Hermosillo was filming Esmeralda Comes by Night (De Noche Vienes, Esmeralda). On location, I met one of my all-time favorite actresses, María Rojo. We watched her excellent performance in Danzon (María Novaro, 1991) while she had her hair and makeup done for her role as Esmeralda. I thought I was time-traveling when I met one of her co-stars, Roberto Cobo, who had played Jaibo in Los Olividados.

In 1997, I spent a week in Mexico City while Hermosillo was filming Esmeralda Comes by Night (De Noche Vienes, Esmeralda). On location, I met one of my all-time favorite actresses, María Rojo. We watched her excellent performance in Danzon (María Novaro, 1991) while she had her hair and makeup done for her role as Esmeralda. I thought I was time-traveling when I met one of her co-stars, Roberto Cobo, who had played Jaibo in Los Olividados.

While Guillermo del Toro lived in Austin, I enjoyed getting to know him. Coincidentally, he had executive-produced Hermosillo's Doña Herlinda and Her Son. In fact, his mother had played Doña Herlinda. I loved del Toro's Cronos (1993), and was honored to be allowed to read an early draft of The Devil's Backbone (El Espinazo del Diablo, 2001). I was truly sorry when he left for Hollywood, but his subsequent films prove that is where he needs to be.

In the mid-1990s, Lara Coger came to AFS with an idea for a Spanish-language film festival in Austin. With the help of Celeste Quesada, Cine Las Americas was born, and I have been on the advisory board for 15 years. Thanks to that wonderful organization, now directed by Eugenio del Bosque, I have now seen hundreds of films from all over Latin America. Digital technology has truly democratized filmmaking in countries where the thought of making a 35mm film was beyond impossible. After 50 years of a wonderful journey through el cine latinoamericano, I'm really happy to be able to present CineSur this summer, naturally including one movie by Jaime Humberto Hermosillo.

CineSur

Thank-you for sharing your love of Latin American films with the rest of us Chale. I do believe it helps to make the world a better and more humane place.