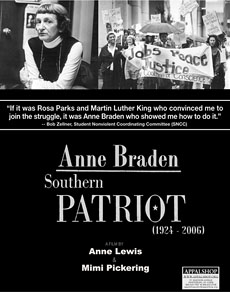

Why You Should See 'Anne Braden: Southern Patriot'

It all started with a tract house in suburban Louisville, Kentucky. Andrew Wade, an electrical contractor and veteran of WWII, and his wife Charlotte tried to buy a new house. After countless rebuffs, one sympathetic realtor suggested that the young African-American couple get a white friend to buy the house and then transfer the deed to the Wades. This was a time when virulent segregation laws were still rigidly enforced in the South (and much of the rest of the U.S.). New suburban developments provided the landing space for white flight from inner cities.

It all started with a tract house in suburban Louisville, Kentucky. Andrew Wade, an electrical contractor and veteran of WWII, and his wife Charlotte tried to buy a new house. After countless rebuffs, one sympathetic realtor suggested that the young African-American couple get a white friend to buy the house and then transfer the deed to the Wades. This was a time when virulent segregation laws were still rigidly enforced in the South (and much of the rest of the U.S.). New suburban developments provided the landing space for white flight from inner cities.

Local journalists Anne Braden and her husband Carl bought the house, signed over ownership, and then the troubles began. First with rocks through the windows, followed by shotgun blasts and burning crosses planted by white-robed KKK members. A bomb explosion finally drove the young couple and their three-year-old child out of the house.

At other times that might have been the end of the whole affair, but it was 1954, the year of the Supreme Court's ruling against school segregation. White racists redoubled their determination to fight any form of integration.

Rather than find the actual person or persons who dynamited the Wade home, a Louisville grand jury charged the Bradens with sedition against the state of Kentucky. Proof? Purchasing a house for an African-American couple in a white neighborhood, explicitly against housing laws and contract restrictions. They were even suspected of blowing up the house themselves in order to enflame racial hatred and stir up a Communist revolution. In December 1954, Carl Braden was found guilty of sedition and sentenced to 15 years in prison. Furthermore, both Anne and Carl were branded "traitors to their race."

Employed as reporters for a local Louisville newspaper, Anne McCarty and Carl Braden had married in 1948. Born in 1924 in Louisville, she had grown up in Alabama and then attended college in Virginia before getting a job as a court reporter in Birmingham, Alabama. Among cases she covered were some involving black men imprisoned for "looking at a white woman in an insulting way" -- in Jim Crow legal terms, "assault with intent to ravish." A Southern, middle-class white woman, McCarty began to feel something wasn't right about such harsh punishments based on the testimony of just one person -- the white woman accuser.

That uncertainty marked the beginning of Anne's remarkable half-century journey into the civil rights movement. Trying to get away from the Deep South, she took a newspaper job in Louisville, Kentucky in 1947. But she soon discovered that racial segregation was just as predominant there. Naturally the whites in power said that Louisville had very good race relations. In short, everyone "knew their place" in society.

Once Anne met Carl Braden, her vague feelings of unease about racial barriers and injustice in the South would take shape. An avowed socialist, Carl Braden was deeply involved in the militant postwar labor movement. After their marriage, Anne combined political activism, a newspaper career, marriage, and motherhood. The "new" Anne Braden became a powerful force for change in the traditions and laws of the South. Together the couple criticized and fought against racism and other social inequities, at a time when most people were subdued into silence by the death-grip Senator Joe McCarthy had on the conscience of America.

The Bradens became part of a much larger civil rights movement in its infancy. Anne was independently writing in black newspapers about white women and racism. But in 1951 William L. Patterson of the Civil Rights Congress told Anne, "You don't need to tell black people about this problem. You need to talk to other white people because they are the problem." That wise advice gave her an entirely new path to explore.

After the Supreme Court ruled in 1956 that sedition was a federal, not a state, crime, Carl Braden was released from prison. The Southern Conference Educational Fund, a civil rights organization, hired Anne and Carl as field organizers and editors of the Southern Patriot newspaper. The couple soon turned that newspaper into one of the dominant voices for civil rights and integration in the South. Within their pages would begin appearing not just the tragic stories of a wide array of "legal" crimes against African Americans, but the signs of a new day brought by the actions of Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, Jr., the NAACP, Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, bus boycotts, sit-ins, freedom riders and death-defying marches. Soon a nationwide movement began attacking the rotten cancer within the American body politic.

Just as MLK began broadening the scope of civil rights by supporting poor people, regardless of race, and speaking out against the raging war in Vietnam, so did the Bradens, who had always criticized capitalism as much as racism. Together with other like-minded people, the Bradens began helping organize blue-collar workers and poor people, black and white, into coalitions in Appalachia.

But with the end of the war in Vietnam, the loss of many student allies in social justice movements, the imprisonment/deaths of many leftist leaders, and changes to laws enforcing segregation in the South and elsewhere, the Movement became far more splintered. Yet even after Carl's death in 1976, Anne Braden continued her involvement in political activism, writing and in support of the righting of social wrongs in America. Some of the issues she dealt with in various ways included school bussing, the murder of five Socialist Workers' Party protestors in Greensboro NC in 1979, apartheid in South Africa, environmental issues, and police brutality. Slowly but surely she finally addressed issues of homophobia within the civil rights movement.

Despite these new issues, her perennial and most consistent issue remained the ravages of racism, a "systemic danger" for both parties, the oppressor and the oppressed. She understood that racism was naturally most devastating for the targeted group, whose lives were twisted, distorted, and unfulfilled. However, she believed that even the perpetrators would suffer devastation of the mind and spirit for practicing or supporting a system that promoted racism. Her voice was silenced only by her death in 2006, but for over 50 years Anne Braden was one of the most important spokespersons for civil and human rights in America.

Fittingly, Austin/Appalachian activist filmmaker/professor Anne Lewis is bringing Anne Braden to a new audience, many of whom may have never been exposed to this white Southern woman's outspoken war on evil inherent in a society which once legitimized the ownership of human beings.

Anne Braden, Southern Patriot is the Doc Night presentation of Austin Film Society on Wednesday, July 18 at 7 pm at Alamo Drafthouse on South Lamar. Anne Lewis will be in attendance for a Q&A session. You can buy tickets and find more information on the AFS website. Watch a sample from the documentary film below.